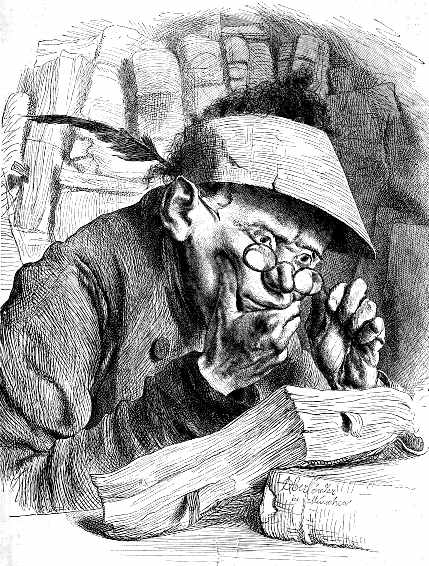

Richard E. Turner (1937-2011)

The Grammar Curmudgeon, a.k.a. “The Mudge”

Rich Turner was a professor, copyeditor, editor, curmudgeonesque grammarian, and beloved husband, father, and grandfather. He was born 1937 in South Africa and passed away 2011 in New Jersey. Starting in 2002 he published grammar and writing tips as well as his own personal essays, articles, and “grumbles” on his website The Grammar Curmudgeon at CitySlide (username grammarmudge). Having hosted the archived site for the past five years, his family will be taking it offline at the end of this month. With their permission I am reprinting two of Mr. Turner’s essays below, so that everyone who has enjoyed his writings and personality can have this online memorial. There are also several quotations from his essays on

The Quote Garden.

An Open Letter to My Grandson

by Richard E. Turner, 1997

When this was written, I had only one grandson. Now, since I have three of them, the title should probably be “An Open Letter to My Grandsons.”

By the time you read this and can understand it, I may not be around anymore. That’s the way it goes, and there’s no point in trying to change things we cannot change. A big part of life is acceptance, or, as someone said, “All you can do is wash up and show up; everything else just happens.”

My first advice is not to give any advice, unless people ask for it. Even then, you may need to figure out whether they really want your advice or merely want you to agree with them (as is usually the case).

Obviously, my advice not to give advice is a self-contradiction. When, as will sometimes happen, you are caught in contradiction, you can always quote Walt Whitman [“Do I contradict myself? / Very well then I contradict myself, / (I am large, I contain multitudes)”] or Emerson [“Foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds”]. Where the rules are clear-cut, consistency is good; where they are not (which is most of the time), consistency may be the sign of a closed mind.

Cultivate openness of mind. It is a rare quality because most of us harbor inflexible biases without realizing that we do. You should, of course, develop a set of values to guide your behavior, but you should be wary of inflicting your values on others (or expecting others to agree with you).

Tend to your own garden; what other people grow in theirs is not your concern, unless their actions harm others. What others believe is their own business, even if it’s diametrically opposed to some of your own most cherished ideas. Besides, your ability to change other people is either highly limited or nonexistent.

This principle applies to religion as well as to morality. If you believe in a Higher Power, that Higher Power is your own, as is everyone else’s Higher Power. You have neither the obligation nor the right to proselytize. The best you can do is develop your own sense of spirituality, follow it with all the integrity you can muster, and let your example speak for itself.

Seek knowledge. Knowing stuff is good. Do this when you are young because your ability to absorb and, especially, to remember will deteriorate sooner than you expect. Recognize, too, that the power of intellect is limited. “Smart” doesn’t account for a whole lot, and it isn’t synonymous with “good” or “happy” or even “successful.”

Although book knowledge is useful, what really matters is what you learn from experience. Observe the world. As Yogi Berra said, “You can observe a lot just by watching.” (You probably have not heard of Yogi Berra; he was a baseball player and manager who had many curious sayings such as this one.)

You may have noticed that children’s powers of observation are quite acute. One reason for this is that, to children, the world is literally wonderful – full of wonder. They see a lot because much of what they see is brand-new. After a while, though, we start to take what was once wonderful for granted – the changing sky, the seasons, the taste of food, the many sounds that we hear each day. We allow distractions that are not really worthy of our attention to divert us from “smelling the roses,” as the cliché puts it. Try to recapture the sense of wonder whenever you can.

Develop the art of listening. Courtesy requires that you listen to what other people say, but you should go beyond this. By listening carefully, you can develop a sensitivity to language and an understanding of how people think and feel. A sense of the magical power of words can benefit anyone, not just writers and editors. And one does not need to be a psychologist to understand the complex internal choreography of thought and feeling that underlies people’s words.

Listen also to the wordless world. Though the world of words may inform your intellect, that which cannot be expressed by words will inform your spirit. Give every form of music a hearing, especially the wordless music that expresses what words cannot, whether in the form of an inspired symphony or the sounds of the natural world. This kind of listening requires no intellectual understanding; it resonates within a part of us that is beyond intellect.

Try to at least start doing these things when you’re young. Resist the natural tendency of youth to live too much in the future, believing that the future is forever. While you cannot expect to be wise and young at the same time, you can avoid the fate of those of us who treat life as a three-act play, doze during the first two acts, and wake, when the play is nearly over, to discover that this is the only performance. We do not, as far as I know, have the chance to rerun our lives.

Numerous metaphors have been used to describe life. Among them is the metaphor of life as a battle. Try not to think of life in these terms because, if you regard life as a struggle, it will become one, and you will have little joy. It is far better to think of life as a journey in which the difficulties are hills to climb. The hills are there for a reason (even if you don’t know what that reason is), and the sense of satisfaction after climbing the hill is almost always worth the effort.

But perhaps the best metaphor is that of life as a river. If you let the current carry you, you will be far better off than if you try to swim against it. This does not mean that it is an effortless ride; some parts of the river will be hazardous, requiring great skill to navigate safely. You will need to learn when to ask someone else to help with the paddling and when to stop paddling altogether.

Finally, and possibly most important, you should take time to see the humor in it all. The world is a funny place, and funniest of all are the creatures who walk about upright on two legs, believing that they run the place. You should not take it too seriously, and that includes what I have written here.

Kindness to Animals

by Richard E. Turner, 2005

Since I am a self-confessed, card-carrying curmudgeon, kindness is not generally considered to be one of my prominent character traits. Nevertheless, we curmudgeons tend to have a soft spot for so-called lower animals because the supposedly higher animals – namely, our fellow human beings – continually distress, disappoint, and annoy us.

We do acknowledge the scientific evidence that our species has appeared to evolve physically more than any other. We admit that the human brain is probably more complex than any other known living brain, although we seriously question the uses to which our species has put this organ, and we often wonder whether some of our kind use it much at all. After all, there must be some reason why the adjective

stupid is more often applied to people than to other animals. As for our supposed sense of morality – the ethics that we presume that

amoral* lower animals lack – the verdict is still out. The most highly developed human brains seem hard-pressed to agree on what is “right” and what is “wrong” in many situations. While we may argue that lower animals cannot do this either, that they live by instincts alone (a hypothesis now being refuted by many scientists), our relativistic morality does not necessarily mark us as superior. An equally valid conclusion could be that it serves mainly to make us more confused.

Be that as it may, even we curmudgeons believe that kindness to animals (meaning, of course,

other animals) is an admirable, possibly ennobling, trait. I’m not talking only about the fuzzy, loveable animals we have as pets. I, for example, am partial to warthogs, although I wouldn’t have one as a pet. Somehow, I feel that any animal that ugly (in my perception of beauty) must have a beautiful soul.** Besides, if warthogs didn’t find each other attractive, there wouldn’t be any baby warthogs, would there? No great loss, you say? Well, that’s your perspective and is not the warthog’s view; nor is it mine.

I suppose that a case could be made against poisonous snakes, vultures, rats, and such creatures, but they are only doing what they must to protect themselves and survive. One can hardly fault a grizzly bear for mauling a two-legged intruder who threatens its young or stands between it and dinner. After all, people clobber and sometimes kill other people for little or no reason. Animals do not wage war, and, though I’m no zoologist, I don’t think many of them kill for the sheer fun of it.

I’ve never understood people who shoot animals for sport. Oddly enough, people who would never think of killing a dog or cat for fun are greatly entertained by killing a deer or bear or elephant that has done nothing all its life but mind its own business. Besides, there are better things to shoot. For instance, when your computer or washing machine has broken down beyond repair, take out your trusty AK-47 or Smith & Wesson and blow that sucker to smithereens. It won’t feel a thing.

What fool thinks that animals don’t feel pain? They have nervous systems and brains. Some of the less-developed species and orders indeed lack central nervous systems (yes, I swat flies and step on ants), but that’s not what we’re talking about here. We’re talking about sentient creatures. We can’t be sure what feelings they have – biologists are still working on that – but their inability to express feelings in words doesn’t mean that they don’t have them. That they can’t shed tears doesn’t mean that they can’t feel hurt, mentally as well as physically. As Mark Twain observed, man is the only animal that blushes – or needs to. Does that mean that other animals can’t feel embarrassment? I swear I’ve seen many a cat or dog, caught in the act of doing something it knows it shouldn’t,

look embarrassed.

One of my fellow curmudgeons, the late Cleveland Amory, wrote that he was forming the “Hunt the Hunters Club,” the motto for which was, “If it’s red and moves, shoot it.” Perhaps I should revive this noble cause.

Still, putting aside the issue of hunting, there’s no reason why we cannot be much kinder to other animals than we are. I confess my regret that I was raised to be a carnivore, and I envy people who can take their kindness toward animals to the limit of eating nothing but plants, especially when I read the horrifying articles about the way some animals are treated before they are slaughtered as food for humans. I don’t like to think about what something I’m eating looked like or how it felt when it was alive. Yesterday’s loveable and attractive animal is tomorrow’s fricassee. Yech!

Still, this is all the more reason for those of us who are habitual meat-eaters to be kind to the animals that live among us and even to those that are fortunate enough to live in the wild, mostly apart from us. As with our own kind, it costs us nothing to try to understand them, to empathize with them as much as is humanly (and humanely) possible, to be gentle and considerate.

To end where I began, we curmudgeons often have difficulty viewing our species as superior, let alone noble. In particular, this curmudgeon feels that the actions of people who are cruel to animals are proof of the human capacity to be barbaric and mean. On the other hand, ironically, people who treat animals with respect, consideration, and kindness give the word

humanity at least one positive meaning.

* For the first time on this website, I am using a word link that takes the user to definitions at answers.com. If you click on

amoral, you will go to sources clarifying that

amoral does not have the same meaning as

immoral (the opposite of moral) but refers to the state of being neither moral nor immoral, of existing outside the context of morality.

** “That’s ridiculous,” you say, “Warthogs don’t have souls.” How do you know? It could be that, when they die, their beautiful souls ascend to warthog heaven, the Great Mudhole in the Sky.

|

| Bookplate of Richard E. Turner |

“Grammar Checker – A software program that is not needed by those who know grammar and virtually useless for those who don’t.” ~Richard E. Turner, “The Curmudgeon’s Short Dictionary of Modern Phrases,” c.2009